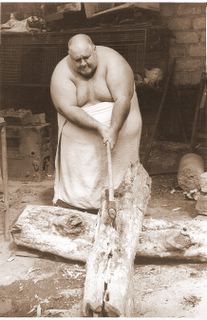

Marxist Austerity Doesn't Deter 580-Pound Man

Marxist Austerity Doesn't Deter 580-Pound ManDavid Abel

Newsday

8/16/1998

CONTRAMAESTRA, Cuba -- Food shortages and inadequate monthly rations force most Cubans to keep a Spartan diet.

But then, Papio Castro is not like most people.

The 63-year-old illiterate private truck driver, weighing in at 580 pounds, is said to be the Marxist state's most well-fed man.

"Many people think we're rich," says Castro, whose extra-wide pants are unbuttoned at the waist and split at the seams.

"But we live for food. We don't bother about the house, or our clothes. Nothing, really, except for food."

The former guerrilla warrior's eating regimen would be impossible on the average Cuban salary of about $8 a month. So several years ago Castro rigged his 1952 Dodge truck to ferry passengers around town, one of the country's few legal private businesses. A network of black marketeers, who sell him a range of foodstuffs from steak to illegal shellfish, further ease the financial burden.

At Castro's small pink house here in the foothills of the island's rugged Sierra Maestra mountains, there are no quickie eat-and-run meals. Breakfasts and late lunches for the gray-haired father of four take time to prepare - and to consume. He snacks on a few well-stacked sandwiches for supper.

A typical breakfast consists of eight or nine scrambled eggs, a half pound of homemade cheese, 40 mangos, two or three pineapples or up to 12 bananas, a half pound of ham, and a liter of sugary milk or fresh-squeezed orange juice, he says.

His mid-afternoon snack usually

involves 12 to 15 scoops of strawberry ice cream. And a filling lunch is often a full five-pound red snapper over two pounds of rice and a side dish of three pounds of extra-greasy French fries.

involves 12 to 15 scoops of strawberry ice cream. And a filling lunch is often a full five-pound red snapper over two pounds of rice and a side dish of three pounds of extra-greasy French fries."He is very demanding," said Castro's portly but less plump wife, Margot, who prepares all his food, boxing it when he goes on the road. "He calls me for everything. If he wants a steak, I make it for him. If he tells me to kill a pig, I kill it."

No official records certify Castro as the island's heaviest man, but state radio and television broadcasts have unabashedly dubbed him "Cuba's fattest man."

The son of overweight parents, Castro weighed about 180 pounds until 1970. That's when he got a job driving a truck for a sugar refinery.

Odd hours and waiting around for deliveries left him spare time to chow on the factory's free food. By the end of the year, he ballooned to 300 pounds.

"I didn't realize I was gaining weight until it was too late," Castro said. "I already had a routine. I couldn't stop eating. It was an addiction."

The large, cheerful man has since steadily widened his perimeter. Last month, he gained 40 pounds. But, still, he and his family insist that he is healthy.

Carmelia, Castro's 33-year-old daughter, is an electrocardiogram technician. She checks his heart every three months and says he has never had high blood pressure or other heart problems. She also rules out a crash diet, saying his enlarged organs might not similarly contract.

"We're not blind about the risks of a heart attack," she said. "It's scary. We love him. But he's happy, and that's what's important."

The greater danger is falling. Stepping out of his truck in late July, Castro lost his footing and crashed on the pavement. His already grapefruit-sized ankle swelled to the size of a pineapple, cooping him up in the house for more than a week.

Though Castro couldn't make the trip to a nearby river to swim, his favorite pastime, the injury left him time to concentrate on his other hobbies: listening to radio broadcasts from the United States, rocking on his specially made oversized chair and, of course, eating.

"I like to eat," he says.

Stretched out on his king-sized bed, which is braced by metal slats underneath two thick mattresses, Castro crunches on several sucking candies recently brought by visitors. He reflects on his life, and says he has few regrets.

"When I die, I have one request: The pallbearers cannot use a car. They have to carry me to my grave," Castro says, chuckling. "I want them to know who I was."

Copyright, Newsday