By David Abel | Defense Week | 2/8/1999

A burst of knocks rattled my bedroom door before breakfast on Christmas Eve. Maria, my host for this and three previous reporting trips to Havana, stepped into the room, her face drawn and pale. "David," she said in a frightened whisper, "the police want to see you."

I walked into the hall half-dressed. "What's the problem?" I asked, as Maria's two young daughters gawked at the stern-faced officials in military uniforms.

"There's a problem with your passport," one said. "You must get your bags and come with us. Right now."

I knew there was no problem with my passport. I arrived the night before to write about the newly legalized Christmas holiday and the 40th anniversary of Fidel Castro's revolution for several U.S. newspapers. But Cuban officials are familiar with my work and don't like what I've written. They wanted me out of the country, and fast.

A nagging omen the same day also made me wonder whether this was the best time visit Cuba: In Washington, the State Department had ordered three of the island’s diplomats to leave the United States for spying.

Scar-faced interrogatorsOn my last trip to Cuba, not long before, security agents called me into a small government office and admonished me for interviewing a couple who opened the island's second "independent" library. It featured taboo books, including George Orwell's "Animal Farm" and "1984."

In that meeting, surrounded by four brawny men inside a cramped, smoke-filled office, the domineering man of rank in an olive-green uniform told me I should no longer visit the middle-aged couple, who had made names for themselves as dissidents in Santiago. The agents had a

different name for the city's alternative librarians. They were terrorists, my interrogator explained. "You don't want anything to do with them," he said, more a warning than a friendly suggestion.

different name for the city's alternative librarians. They were terrorists, my interrogator explained. "You don't want anything to do with them," he said, more a warning than a friendly suggestion.Then he took out a crumpled fax. He began reading a translated version of a story I wrote about a crackdown on newly sanctioned private businesses. "Lies!" he shouted between paragraphs. "These are all lies!"

To be sure, many might take the hint, that returning to Cuba would not be a wise idea. But for a journalist -- a person who tests authority for a living -- the logic was the opposite: If they didn't throw me out of the country then, why would they mind if I returned now?

Still, I never expected that less than 24 hours after landing in Havana, I would be escorted to an old Soviet propeller plane and whisked back to the Bahamas.

Rationing visas

Technically, they had every right to send me on my way. Cuba requires that reporters get a special visa before entering the country. Knowing the visa-rationing process often excludes journalists with a history of writing critical stories, I went on a tourist visa -- the choice of many of my colleagues.

The U.S. government, which in effect bans most Americans from traveling to Cuba, makes an exception for journalists.

The night before Christmas Eve, all seemed to have gone as planned. After flying in from the Bahamas, one of the easiest ways to get to Cuba from the United States, I cleared customs in Havana without a problem.

The woman stamping passports didn't even ask my profession, as is the norm. In the past, I would say I was a writer, which is true, but carries a less threatening connotation than the title "journalist." To tell a Cuban official you're a U.S. journalist is tantamount to declaring you're an enemy, or at the least, someone to be watched.

A Cuban-American man I met during the flight offered to take me into Havana. After bribing his way past airport officials to avoid paying extra for the 66-pound limit on baggage, the man's cousin picked us up in one of the island's many battered but not bygone American classic cars from the 1950s.

We puttered away from the new Canadian-built Jose Marti International Airport, past motor oil advertisements next to billboard propaganda with slogans such as "Socialism or Death." A half-hour later, after passing the sprawling Plaza de la Revolucion and a row of skin-advertising jineteras (prostitutes) headed toward the downtown hotels, we arrived in the upscale Vedado district at Maria's once-stately, now decayed five-bedroom home.

The family was up late waiting for me. We hugged, tipped back shots of Havana Club rum and chatted about the upcoming Christmas celebrations. No one could have expected that I would be gone the next morning.

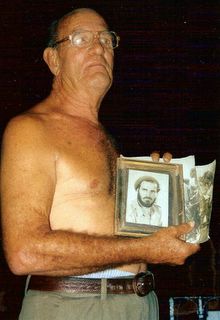

Especially Paco, Maria's father-in-law.

On many occasions during the nearly two months I stayed at their home on Fourth Street, the 71-year-old former guerilla warrior repeatedly spouted the government line that Cuba was a free country where people said and did what they wanted.

On many occasions during the nearly two months I stayed at their home on Fourth Street, the 71-year-old former guerilla warrior repeatedly spouted the government line that Cuba was a free country where people said and did what they wanted.So it came as a surprise when two sleepless officials showed up early the next morning and ordered me to start packing. I asked them what was the problem, but they said they didn't know. Orders had come from above.

As I thanked the Gonzalez's for my brief stay, Melinda, Maria's 9-year-old daughter, welled up with tears and couldn't look me in the eyes as she hugged me goodbye. Like her mother, she thought I'd done something wrong. Someday they'll understand my crime. It's called telling the truth.

The officers escorted me to their rickety Soviet-made Lada patrol car. Inside was a woman also in official military regalia. She was the same immigration officer who checked my passport the night before. She hadn't slept, she said, and then scolded me for not giving her my Havana address.

Flanked in the backseat by the immigration agent and another apparently drowsy officer, none could explain the sort of "passport problems" I had. They did, however, pepper me with questions, such as: "What did you do last night?" "Did you contact anyone?" "Why didn't you tell us you sent an electronic mail?"

At the airport, I was told to wait to see another official. An hour later, the jefe, or boss, hadn't shown. I started to sweat. Six newspapers throughout the United States and Canada were waiting for my story about Cuba's Christmas celebrations, which returned for the first time as a legal holiday since Castro abolished its observance in 1969.

If I were going to be deported, which at this point seemed certain, I wanted to go soon. The longer I sat around watching Russian tourists filter through immigration booths and being watched by goons in fatigues, the less likely I would have been able to file my stories.

So I told them I was hungry. The officials had my passport and plane ticket; they weren't worried about me running off. They let me go to the upstairs terminal, where I found a small cafeteria -- and an outlet for my laptop. Within an hour, I wrote a story about my short stay with the Gonzalez's.

The final insult

Except a while later, the file disappeared. The officials at the gate made sure I put my bags through a special X-ray machine. They also scoured my luggage by hand, and chided me for being a "counterrevolutionary" when they found a biography of Fidel Castro, a travel book called "Waiting for Fidel" and another , more damning book called "Castro's Final Hour."

Afterward, waiting at a bar with maracas and Che Guevara T-shirts on sale for departing tourists, I discovered only rows of the letter "y" in the computer file where my story had been saved. I figured that was the final insult.

Then a young man with epaulets on his uniform led me across the open tarmac to the waiting prop plane. We joked about me escaping, but I said I didn't have the energy.

"Why are you being deported?" he asked.

"I'm not sure," I shrugged.

"What do you do for a living?" he prodded with a hint of understanding.

"I'm a writer," I said.

The skinny Cuban smirked, handed me my passport and ticket, and before watching me climb a wobbly staircase into the belly of the empty plane, he said, "I don't think you should come back to Cuba."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.