By David Abel | Miami New Times | 2/15/1998

By David Abel | Miami New Times | 2/15/1998Wearing his best shirt and clasping hands with his wife and two young sons, Diosmel Rodriguez Vega entered America with a strained smile that melted into tears as supporters surrounded him at Miami International Airport. After the hugs and cheers, a throng of journalists pressed forward to interview the slight, bespectacled man. The exiled dissident didn't mince words. "I had no intention of abandoning my country," he said as he made his way through the terminal that August afternoon in 1997. "The government said I was persona non grata and that I couldn't continue living in Cuba. They told me I had to leave."

The previous month state security agents had arrested the 44-year-old Rodriguez at his home in the eastern city of Santiago de Cuba and taken him to prison. But the authorities couldn't send the former army accountant and onetime government statistician off to anonymous detention, the fate of many political prisoners; Rodriguez had already made a name for himself in the foreign press.

An outspoken critic of the Castro regime, he had organized scores of followers in 1993 who handed out leaflets urging voters to boycott that year's presidential elections. For "distributing enemy propaganda," he was sent to Santiago's infamous hilltop Boniato prison, where Castro himself once served time for rising up against Fulgencio Batista. But in prison Rodriguez attracted even more media attention. From 1993 to 1996 he went on a dozen hunger strikes, one of which lasted 40 days.

So in July 1997, authorities kept him in custody for just a week before telling him he had fifteen days to pack his belongings, obtain U.S. visas for his family, say goodbye to relatives and friends, and leave Cuba forever. "They said I was a suspicious person, that I was spreading false rumors abroad that there was an outbreak of conjunctivitis in Santiago," said Rodriguez, making sure reporters took note of the inflammation in his younger son's and wife's eyes. In fact he'd written articles on the outbreak of dengue, another extremely contagious disease, for an exile-run Internet news service in Miami. Then he added: "They said nothing about the resistance, even though it's becoming the largest movement on the island."

Rodriguez held his little boys tightly. His wife, overwhelmed by the barrage of cameras and microphones, told reporters she was nervous and hoped now the family would have a little peace. But the dissident still had his mind on rebellion. One day, he said, he would return home. "What we have done is nothing less than create a tremendous resistance against the government ... and lay the foundation to create true social justice."

THAT RESISTANCE, WHICH FORCED the Rodriguez family into exile, threatens to strike at the heart of Cuba's economy: Private farmers in three provinces have organized independent collectives and are refusing to do business with the government.

How did a military man come to lose faith with communism and persuade farmers across the country to join him in nonviolent rebellion? His views began to shift in the Seventies, after he'd graduated from Santiago's Oriente University, he said in an interview late last year. Rodriguez was among the hundreds of thousands of Cubans sent to Angola in support of the Marxist Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola during that country's civil war. By day, as accountant Rodriguez reviewed army expenditures, Cuban soldiers were brought back from the fields limp and bloody, he recalls; by night the generals and bureaucrats swilled Havana Club and smoked Cohibas sent from the island especially for them.

When he returned home to Santiago in 1980, Rodriguez left the army and became head statistician of the province's Ministry of Construction. But the pay, about thirteen dollars per month, was barely enough to live on. So like many accomplished Cubans, he quit his government post to take a less prestigious but better paying job. He found work as a state-licensed taxi driver, earning more in a week than he did per month in his previous position. "As a taxi driver, I was exposed to a lot of people," he recalls. "I got to learn the way they think — everyone from professionals to marginal people — and that helped me develop my political ideas." He also credits the U.S. operated Radio Martí, as well as a steady stream of anti-Communist articles in newly critical Soviet newspapers that made it to Cuba in the late Eighties. In 1989 he quit the Communist Party altogether. "I started to question the system," he explains. "There's a point when you can no longer be passive. You have to act." "We wanted to let the campesinos know it isn't wrong to sell your merchandise for the price you want, to the place you want."

Three years later he organized a small political party, the Followers of Chibás Party, named after Eduardo Chibás, the senator who in 1951 committed suicide following a national radio address to awaken Cubans to his calls for social justice. Rodriguez and fellow party members began distributing thousands of leaflets in Santiago, first before the December 1992 provincial elections and then in advance of the February 1993 presidential vote. But the government seized the pamphlets and threw Rodriguez into prison. When they released him in 1996, he was blackballed from employment and forced to rely on relatives to stay alive. Unrepentant, he resumed his political activities, reorganizing and renaming his party. He drafted a new platform, the "Popular Program of National Salvation," which called for democracy, free markets, and a return to the ideals laid out in Cuba's 1940 constitution.

Like Chibás, who once mentored Fidel Castro in politics, Rodriguez set out to galvanize grassroots support. But rather than recruiting professionals and intellectuals in Santiago, as he'd tried before, this time he left the city and ventured into the crinkled peaks and emerald valleys of the coastal Sierra Maestra mountains, where José Martí had led his uprising against Spain and where Castro armed peasants to overthrow Batista. The impoverished campesinos in the remote hills surrounding Santiago have long been known for asserting their independence. And Rodriguez believed that the region's private farmers — a small group who owned their land and who had gained much at the outset of the revolution, only to lose almost everything four decades later — might take a stand with him against the state's rigid controls.

"It's not easy to motivate people to fight," he said in his cramped apartment near Miami International Airport. "Cubans are so drowned in politics, it's the last thing they want to think about. People would prefer to get on a small boat and risk their lives rather than organize against the government.... But this was a cause people could believe in. It's about the right to live and eat."

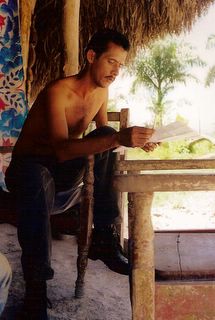

Eventually he tracked down Antonio Alonso Perez,

a former Chibás Party member who'd fled Santiago after the government crackdown. He found the 33-year-old engineer living in squalor with his wife and four boys atop a lush hill in Loma del Gato, an almost inaccessible section of the Sierras crisscrossed by hundreds of acres of state farmland abandoned in the post-Soviet "special period." A poorly thatched roof covered the family's one-room home; the walls were built of branches and caked mud; there was no electricity. They had to walk at least a mile to fetch water from a local stream, and even farther to the nearest village, Songo-La Maya. Their prize possession: an old Soviet-made, battery-powered radio.

a former Chibás Party member who'd fled Santiago after the government crackdown. He found the 33-year-old engineer living in squalor with his wife and four boys atop a lush hill in Loma del Gato, an almost inaccessible section of the Sierras crisscrossed by hundreds of acres of state farmland abandoned in the post-Soviet "special period." A poorly thatched roof covered the family's one-room home; the walls were built of branches and caked mud; there was no electricity. They had to walk at least a mile to fetch water from a local stream, and even farther to the nearest village, Songo-La Maya. Their prize possession: an old Soviet-made, battery-powered radio.Alonso, whose family has owned a 40-acre farm since 1926, was living quietly, growing corn, coffee, and other crops. Extreme destitution and bitterness, however, made him receptive to Rodriguez's plans for an agrarian revolt. The two men fanned out in Loma del Gato to try to persuade Alonso's neighbors to join them. They avoided speaking in political terms. "All we want, we explained, was to let the campesinos know that it isn't wrong to want to sell your merchandise — the products of your choosing — for the price you want, to the place you want," Rodriguez recounts. Eventually ten farmers of Loma del Gato agreed to join Alonso and refused to turn over their harvests or otherwise do business with the state. It was a risky stance, as the government is the sole supplier of seeds, fertilizers, and equipment. Their only weapons would be borrowed plowshares and the labor of underfed cattle.

Over the next few months the united peasants, who controlled about 400 acres, began calling for changes in local and state agricultural policies. They rose before local workers' councils to demand growers be allowed to decide what crops to plant. They argued for an end to quotas and price fixing. And they pleaded for the right to be able to sell their crops to whomever they chose. "This system is slavery. [Farmers] work for the state like slaves. They put you in jail if you lose a cow. It's my cow!"

The following year, in May 1997, the ten families of Loma del Gato took a bolder step. They formed a collective, calling it La Cooperativa Transición, and began to share equipment, labor, and long-term plans. Transición called for the right to sell directly to foreign markets, to hire paid labor, and raise and slaughter cattle and other livestock at their discretion. (The unauthorized killing of a cow carries a penalty of up to twenty years in prison. If someone steals a campesino's cow, a common offense in the countryside, the farmer who loses the animal must pay a 500-peso fine.)

Rodriguez and Alonso also took their message beyond Santiago, and in September 1997, campesinos in Bejuquera de Filipinas, in Guantánamo province, banded together to create their own independent cooperative, Progreso I. By then, of course, Rodriguez was in exile in Miami. The next month, Transición and Progreso I united under an umbrella organization, La Alianza Nacional de Agricultores Independientes de Cuba (the National Alliance of Independent Farmers). In February 1998 farmers in San José de las Lajas, in Havana province, formed a third group, Progreso II, and joined the alliance. From Florida Rodriguez can do little more than send about a hundred dollars each month to support expenses for items such as seed and fertilizer.

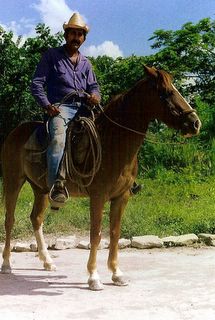

"We want to put the products on the market that are in our interest," says 53-year-old Jorge Bejar Baltazar,

president of Transición, while checking the coffee crop on a portion of the cooperative's 400 acres this past summer. "We want the right price for our work. We should have a say in this. Now the state tells us what we get.... We're working barefoot, poorly dressed, and without food. We want liberty."

president of Transición, while checking the coffee crop on a portion of the cooperative's 400 acres this past summer. "We want the right price for our work. We should have a say in this. Now the state tells us what we get.... We're working barefoot, poorly dressed, and without food. We want liberty."Bejar and Alonso, the cooperative's vice president, were not timid about promoting Transición's goals. They sent letters to party officials; to the president of the National Assembly (the island's congress); and to the president of the National Association of Small Farmers, which regulates private farms like Alonso's. In retaliation they have been summoned for questioning at police headquarters in Songo-La Maya, in the valley below Loma del Gato, and subjected to harassment.

"This system is slavery," Bejar says. "[Farmers] work for the state like slaves. They put you in jail if you lose a cow. It's my cow! Is that not an abuse of power? Here you're the boss of nothing. If tourists want to buy something from me, I should be able to sell it for the price I want."

EACH FARM MUST SELL UP TO 80 percent of its harvest to the state at a fixed price. The remaining 20 percent may be divided between what the family needs and what it can sell at government-controlled farmers' markets, known as mercados agropecuarios. The markets, which had been shut down for nearly a decade, reopened in 1994 as an emergency measure to motivate farmers to make more food available during the shortages after the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991. Like many growers throughout Cuba, members of the independent cooperatives say they want to sell a greater percentage of their harvests at the mercados. (Since 1997 they've been barred from selling at the farmers' markets altogether.)

The farmers complain, too, about the significant disparity between what the government pays farmers and what it later charges its own consumers. A farmer who grows mangoes can expect to get 7 pesos (about 35 cents) per 100 pounds from the state, which then sells the same quantity to consumers for 50 pesos. For milk, a scarce commodity in Cuba, the government pays farmers less than two cents per liter but charges consumers more than a dollar, almost three days' worth of the average monthly salary of less than ten dollars. For a valuable product such as tobacco,

the margin widens even further between wholesale and retail prices, especially when the target market is tourists, who number more than a million per year and who in 1997 pumped more than one billion dollars into the island's economy. Tobacco farmers earn about 150 pesos, or $7.50, for the equivalent of a box of 25 Cohibas. Tourists spend around $300 per box for the famous puros. More than half of the nation's farmers took title to the land they worked. It created one of communist Cuba's nagging aberrations.

the margin widens even further between wholesale and retail prices, especially when the target market is tourists, who number more than a million per year and who in 1997 pumped more than one billion dollars into the island's economy. Tobacco farmers earn about 150 pesos, or $7.50, for the equivalent of a box of 25 Cohibas. Tourists spend around $300 per box for the famous puros. More than half of the nation's farmers took title to the land they worked. It created one of communist Cuba's nagging aberrations.Forced compliance is another issue. At the beginning of the growing season, an official visits each farm to draw up a contract for the coming harvest. The farmer is told not only what to grow, but how much the state expects. The farmer who doesn't meet his quota faces a fine (barring a natural disaster, such as a hurricane.) If a coffee farmer, for example, must deliver 100 cans of coffee beans at the end of the month but only delivers 80, he is fined the price the government would have paid for each, multiplied by ten pesos.

Central planning, bureaucratic management, and little room for individual initiative, Bejar says, have stalled the agricultural economy. "Some have managed to carve out a little autonomy in the system and produce farm products at subsistence levels while secretly selling whatever they can in an underground economy to survive," he explains. "But this is no way to live, and no way for an economy to produce enough food for its people."

Once Transición has acquired enough profits, members hope to build new homes and modern irrigation systems, electrify their farms, and purchase tractors and trucks. But that goal is distant at best. The problem, of course, is money. The Cuban constitution doesn't specifically ban the farmers' actions, Bejar and other cooperative members insist, but faced with official opposition and harassment, and only a trickle of cash from Miami, the farmers have made do with what they can buy and sell on the black market. People often walk long distances and climb steep hills to buy their yuca, corn, taro roots, or avocados. But the trips are worthwhile; the farmers' prices undercut the government's, even those at the mercados.

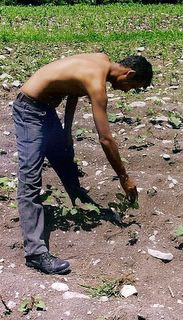

Since he joined the cooperative, Alonso has scraped by, earning a monthly average of about ten dollars, roughly the same as he brought in while working for the state. With the added incentive of cooperatives selling as much as they can produce, he believes they could become profitable and ultimately surpass production of state cooperatives. "Almost 40 years have passed, and we're witnessing the massive level of impoverishment to which our entire nation has fallen," he said while leading a tour of his farm this past year. "We've gone to meeting after meeting, and nothing has come out as a solid accomplishment for farmers. We've been told the same tall tale that draws on history and has no future. Well, we could wait no longer."

THE SEEDS FOR THE CURRENT UPRISING, ironically, were sown by Fidel Castro shortly before he seized power in 1959. Still leading the battle against Batista from his Sierra Maestra mountain hideout, he acted on a promise he'd made five years earlier, during a speech to the judges who condemned him for his bloody attack on Santiago's Moncada army barracks. At the time he denounced Cuba's prerevolutionary agricultural system, which left many peasants undernourished, unemployed, and under constant threat of eviction.

So he signed into law a radical reform granting tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and squatters titles to the land they worked. The decree tripled the number of the island's rural private-property owners, with more than 50 percent of the nation's farmers finally owning their own plots. It also created one of communist Cuba's nagging aberrations.

Since then the government has whittled away the peasants' holdings. In 1963 Castro announced a second agrarian reform, which limited private farms to 165 acres. Those that exceeded the limit were simply expropriated and eventually incorporated into Soviet-inspired massive state farms. He introduced restrictions on farm operations as well. Farm owners could only sell their land to the government; they could not decide what crops to plant, nor could they buy seeds, fertilizers, or tools from anyone but the state. They had to sell the major portion of their harvests to the state at fixed prices. Later regulations included fines for not honoring government contracts, limits on the amount buyers could purchase, sales taxes, and an annual tax on gross income.

As Soviet influence neared its peak in the mid-Seventies, the state pressured all private farmers to sell their land to state farms, which by then accounted for more than 80 percent of Cuba's arable land. (The Alonso family remains among the approximately four percent of the island's farmers who have refused the state's repeated prodding and are still private landowners.) But after food-production shortages and a worsening general economy that culminated in the Mariel boatlift in 1980, the Castro regime reversed its policy. The few remaining independent farmers were encouraged not to sell their land to the state after all, but to combine their assets by pooling their farms' resources and forming government-run cooperatives. In exchange they were promised modern housing, schools and health facilities, low-interest loans, and priority access to machines and construction materials. After Transición declared it would no longer sell its harvest to the state, each family was fined 500 pesos.

Today there are three types of government-sanctioned farms that make up the island's agricultural sector. The state farms, once predominant, are run by the Ministry of Agriculture. Now, however, the state farm system comprises less than 30 percent of Cuba's arable land. Years of overworking the land and the allure of city life have left tracts of land, like those near Alonso's farm, lying fallow.

The second, and most prevalent agricultural organizations are the government-run cooperatives. There are two basic kinds: those whose members lease the land they farm, and those whose members own their land. Together they control approximately 51 percent of the island's arable land.

Unlike Diosmel Rodriguez's independent cooperatives, the state-run cooperatives sell most of their production to the government, harvest what they are told to plant, and remain part of a looser, but still centrally planned, economy.

The third allowable agricultural sector includes the private farms, which account for about fifteen percent of the land. But most of those belong to Credit and Service Cooperatives, formed in 1961 for those who wanted to take advantage of government resources but didn't want to give up their land to the state farms. The remaining landowners, like Alonso, have had little association with the state other than production contracts and the myriad rules and regulations.

Despite the incentives and promises offered by the government in the early Eighties, the independent farmers refused to relinquish control of their land. And according to a University of Havana study from 1990, they complained about the cooperatives' low profitability and insufficient autonomy. Besides, the creation of the mercados agropecuarios in 1981 — which for the first time since the revolution allowed supply and demand to determine profits, and where they could earn extra income — added to their resolve. But five years later the government closed the mercados in a further effort to coerce farmers into joining the state cooperatives.

"The day is not too far off ... when we can say that 100 percent of [private] farmers are in cooperatives," said Castro in a 1988 speech. "We are waging a battle against them."

Food shortages that accompanied the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba's primary benefactor, would bring back the mercados agropecuarios in 1994. But there were differences. Cooperative members could sell surplus produce, but now they needed state certificates proving they had met their established quotas, and a fifteen percent tax was added to their market sales. Although the government has admitted the failure of central planning by replacing the state farms with government cooperatives and bringing back the mercados, the independent farmers believe the reforms were too little too late.

A week after Transición declared it would no longer sell its harvest to the government

in a letter sent to Cuba's National Assembly President Ricardo Alarcón, in May 1997, each family was fined 500 pesos (nearly three months' salary) for "improperly using the land," Alonso says. Bejar was fined an additional 350 pesos for having the improper ratio of male-to-female cattle. Then officials banned the operator of the village's lone tractor from entering Transición farms. And word began to spread, as often happens when dissidents become too vocal in Cuba, that the cooperative members were "enemies of the state," "agents of foreign influence," even "terrorists."

in a letter sent to Cuba's National Assembly President Ricardo Alarcón, in May 1997, each family was fined 500 pesos (nearly three months' salary) for "improperly using the land," Alonso says. Bejar was fined an additional 350 pesos for having the improper ratio of male-to-female cattle. Then officials banned the operator of the village's lone tractor from entering Transición farms. And word began to spread, as often happens when dissidents become too vocal in Cuba, that the cooperative members were "enemies of the state," "agents of foreign influence," even "terrorists.""They're doing something they shouldn't," said Hieronide Plana this past summer. The 73-year-old lives with his wife in a tiny house without a roof a few miles from Alonso, where he still works as a private farmer and operates within the system, selling his produce to the state. "The people are obliged to cooperate with the state to work for the benefit of everybody," he added. "Before the revolution there was no security. Now everyone has something to live on.... I have a doctor, a pension, and two educated daughters who are high school teachers. That wouldn't have been true before the revolution. People have to work together, not for themselves. What they're doing threatens our system."

THAT AUGUST, AFTER RODRIGUEZ was forced into exile, officials summoned Bejar and Alonso to Songo-La Maya and expelled them from the island's small-farmers association. "They mounted a show trial of sorts, where all they did was insult me and present all sorts of lies about me," Alonso said. "They were set on expelling me because they said if they didn't, our views could infect the others." The two Transición leaders and their neighbors were later interrogated at the village's police headquarters. Province officials later undertook what amounted to an internal economic blockade. It became impossible for the independent cooperatives to buy seeds, fertilizers, and tools, or to use heavy machines. And unable to get the proper certificates, the cooperative members could no longer sell their produce at the mercados. Officials forced Hernandez to uproot a tobacco crop; he was, they said, using improper seeds.

But the farmers were not discouraged, even as they struggled to survive. Alonso prepared to celebrate

the first anniversary of Transición last year at his farm in Loma del Gato. He planned to invite members from the other independent cooperatives and independent journalists as well, but the festivities never took place. Reynaldo Hernandez Perez, president of the cooperative's umbrella organization and leader of Progreso I in Guantánamo, was arrested in Havana while delivering invitations. Two days before the party Hernandez was arrested again. The government also arrested Bejar and summoned Alonso and a half-dozen cooperative leaders to police headquarters. Police even barricaded the path up to Loma del Gato.

the first anniversary of Transición last year at his farm in Loma del Gato. He planned to invite members from the other independent cooperatives and independent journalists as well, but the festivities never took place. Reynaldo Hernandez Perez, president of the cooperative's umbrella organization and leader of Progreso I in Guantánamo, was arrested in Havana while delivering invitations. Two days before the party Hernandez was arrested again. The government also arrested Bejar and summoned Alonso and a half-dozen cooperative leaders to police headquarters. Police even barricaded the path up to Loma del Gato.This past October the authorities again called Alonso and two other Transición members to Songo-La Maya, where security agents warned them they could be tried for "illegal" activities. A month later in Las Tunas, police interrogated and threatened a member of the National Alliance of Independent Farmers; in Guantánamo, officials forced Hernandez to uproot a recently planted tobacco crop after they said he was using improper seeds. While the government has yet to shut down the farmers' experiment, the atmosphere in the Sierras remains tense.

But Rodriguez is committed to expanding his movement and believes his path is the future. "The government has condemned us to dragging the same chains that have weighed us down for so many years," he maintains. "The only answer is to organize and to stay committed to our goals of a Cuba where the people control the government, and the government ... does not control the people."

Copyright, NewTimes, Inc.