By David Abel | The San Francisco Chronicle | 11/15/1998

LOMA DEL GATO, Cuba - The long, muddy trail down from Antonio Alonso Perez's thatched-roof shack passes stretches of abandoned state farms and leads to an emerald valley where once-friendly villagers now slam doors and turn their backs on this dissident vegetable farmer.

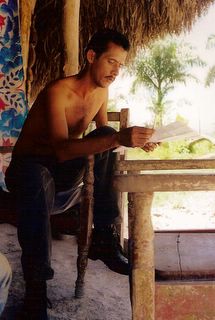

The 34-year-old father of four, who lives in a one-room hovel made of tree limbs and packed dirt, is among a growing group of restive farmers that the authorities have branded as subversives bent on corrupting the country.

"They say we shouldn't let them into our houses," says Nanci, 30, who lives along the trail and is afraid to give her last name. "They say they will bring problems. That they are counterrevolutionaries."

Forty years after Fidel Castro incited peasants here in Cuba's heartland to take up arms against the government, Alonso and hundreds of farmers across the island are rising up against Castro's government. This time, however, their weapons are borrowed plowshares and the labor of skinny cows.

The lanky farmer's rebellion began on May 5, 1997, when he and 10 peasant families founded a work cooperative named Transicion and declared they would no longer do business with the government.

The goal of the cooperative was to foster drastic changes in Cuba's agricultural policy of four decades. Transicion, soon joined by two more cooperatives in Guantanamo and Havana, has demanded the government allow farmers to decide what crops to plant, end fixed prices and quotas, and let farmers sell their merchandise where they want and to whom they want.

The farmers also want to sell directly to foreign markets, to hire paid labor, and to raise and slaughter cattle and other livestock at their discretion.

"Forty years have passed and we are witnessing the massive level of impoverishment to which our entire nation has fallen," Alonso said, while checking the coffee crops on his portion of Transicion's 400 acres of land.

"We have gone to meeting after meeting, and nothing has come out as a concrete accomplishment for farmers. We have been told the same tall tale that draws on history and has no future. Well, we could wait no longer," Alonso said.

In Communist's Cuba's centrally planned economy, farmers have little choice but to comply with the state's wishes. Independent farmers like Alonso, those not working on a state farm or a government-sanctioned cooperative, are obliged to sell up to 80 percent of their harvest to the state at a fixed price, well below what they would earn on the market.

Those who do not fulfill their government contracts can be slapped with stiff fines. The renegade farmers believe it's unfair the state pays them a fraction of what it charges consumers for their produce.

If they grow mangoes, for example, the farmers can expect about 7 pesos (35 cents) per 100 pounds from the state, which sells the same quantity to buyers for 50 pesos.

For milk, the government pays farmers 35 centavos (100 centavos makes one peso) per liter and then charges consumers about 25 pesos. And for a high-end product like tobacco, farmers earn about 150 pesos, or $7.50, for the equivalent of a box of 25 Cohiba cigars. The government gets as much as $300 a carton for the famous puros in hotels and other places where tourists shop.

'We want to put the products on the market that are in our interest. We want the right price for our work. We should have a say in this," says Transicion president Jorge Bejar Baltazar, 53, who wears a straw Stetson, spurs on his mud-caked boots and whose education ended at the eighth grade.

Bejar and Alonso, the cooperative's vice president, have not been timid about promoting Transicion's goals. And the government's response came swiftly.

A week after the members of Transicion declared their independence,

officials fined each family 500 pesos - about three months' worth of an average Cuban's pay - for "improperly using the land," Alonso said. Shortly after, Bejar said, he was fined 350 pesos for having the improper male-to-female ratio of cattle. Both he and Alonso said they were also expelled from a small farmers association.

officials fined each family 500 pesos - about three months' worth of an average Cuban's pay - for "improperly using the land," Alonso said. Shortly after, Bejar said, he was fined 350 pesos for having the improper male-to-female ratio of cattle. Both he and Alonso said they were also expelled from a small farmers association.Among other forms of harassment, including interrogations of cooperative members at the local police headquarters and warning villagers not to associate with these "agents of foreign influence," officials made it difficult for the farmers to operate.

The tractor that tilled many of the cooperative's fields was banned from entering their farms and the black market soon became the only means of buying seeds, fertilizers and tools, obtaining heavy machines and selling produce.

"They're doing something they shouldn't," said farmer Hieronide Plana, 73, one of Alonso's neighbors who sells the vegetables he grows to the state.

"The people are obliged to cooperate with the state to work for the benefit of everybody. Before the revolution, there was no security. Now everyone has something to live on. ... What they are doing threatens our system."

But cooperative members believe they are working within the system. They say the seeds of their rebellion were planted by Fidel Castro just before he seized power on Jan. 1, 1959. Still in his Sierra Maestra secret headquarters not far from Loma del Gato, the bearded rebel signed Revolutionary Law 1, granting tenant farmers, sharecroppers and squatters title to the land they worked.

The act, which sanctioned privately owned farms like Alonso's, tripled the island's number of rural private-property owners, leaving more than 50 percent owning plots.

Today, however, fewer than 4 percent of farmers are landowners. Over time, as Communism took a foothold in Cuba, Castro's regime pressured the new class of private farmers to give up their newly acquired land and join the Soviet-modeled state farms or pool their plots with other farmers to form government-managed production cooperatives.

While many willingly joined the socialist economy, and benefited from state-subsidized housing, schools, health facilities, day care centers and guaranteed pensions, a sizeable group refused to leave their land.

The emergence of farmers' markets in 1981 - which for the first time since the revolution allowed supply and demand to determine profits, and significantly boosted private farmer's income - increased their resolve to remain on their own.

Despite continued efforts to integrate the holdouts, the antagonism increased in 1986 when Castro closed the markets and promised to "wage a battle" against the private farmers, claiming they had become millionaires. (Alonso says he scrapes by on about $10 a month.)

Though the markets returned in 1994, after massive food shortages followed the collapse of Cuba's prime benefactor, the Soviet Union, the tension remains.

"The Transicion cooperative isn't just a piece of land and a band of farmers. It's an idea, a goal, the age-old dream of peasants which can now become a reality by directly defying those who would deny us the most basic right of all - the right to eat," says Diosmel Rodriguez Vega, who founded the cooperative movement after being released from a three-year prison sentence in1996 for "distributing enemy propaganda."

"We cannot continue waiting for government approval. To do so would condemn us to dragging the same chains that have weighed us down for so many years."

For Alonso, who has his phone calls interrupted by government monitors and often confronts scowling officials along the winding trail to his modest mountaintop home, the tension is no longer an issue.

"What else can they do to me?" he wondered. "They follow me, harass me and have taken away almost everything I have. I won't let them take away my dignity."

Copyright, The San Francisco Chronicle