|

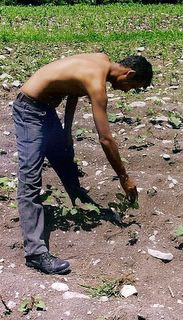

| Cuba's revolutionary pains: Many Cubans, from former guerrilla fighters to those living in exile, feel Castro's 40-year rule has fallen short of the paradise he promised. |

By David Abel | The Ottawa Citizen | 12/13/1998

SANTIAGO DE CUBA, Cuba -- Forty-two years ago, Reinaldo Gonzalez Santana learned through the peasant pipeline that a band of bearded men combing through the Sierra Maestra mountains not far from his small shack were leading a rebellion against the island's thuggish dictator.

As he heard more about the uprising and saw many of his neighbors head into the hills with rifles, the destitute farmer was swept up in the call for a return to democracy and social justice. So it wasn't long before Mr. Gonzalez himself was roving the countryside with the armed rebels and launching attacks against the corrupt regime of Fulgencio Batista.

When the guerrilla warriors' two-year campaign finally met success on New Years Day in 1959, the hardened rebel returned home a hero and was cheered by jubilant crowds. But the euphoria of victory quickly wore off as Mr. Gonzalez watched his revolution for democracy veer off toward one-man rule and communism.

"They lied to us to get our support," says Mr. Gonzalez, now 74, who adds he would have left if he had the money and could bring his whole family. "Now, they can put me in jail for talking like this. But what do I care? I have nothing left for them to take away. No one has anything, except the generals and Party chiefs. For 40 years we have this guy. He's worse than Stalin. It's time for a change."

As Cuba observes the 40th anniversary of Fidel Castro's ascension to power -- a reign longer than any other Latin American ruler this century -- most Cubans struggle to put enough food on the table, dwell in crumbling buildings and thousands plunge regularly into the seas hoping to join the 1.3 million Cubans already living in the United States.

Even though the island's economy remains in tatters -- devalued by as much as 40 per cent after its benefactor, the Soviet Union, dissolved in 1991 -- and 450,000 applied for U.S. visas just this year, a cadre of loyal Fidelistas remain steadfast in support of their "maximum leader's" call for "socialism or death."

One such card-carrying Communist is Jose Martinez, a 54-year-old engineer from Santiago, the island's second city on its southeast coast. The grey-haired father of two lives in the only freshly painted home on B Street. A few doors down his unpaved road, one of Mr. Martinez's neighbours, a doctor, can't practise medicine because he was caught trying to escape the island; another, a septuagenarian, won't tell a reporter his name for fear of government reprisals; and another neighbor in a ramshackle home dreams of one day joining her children in Miami.

Mr. Martinez, a gentle man who devoutly believes in the revolution, holds a minor, but significant post in the Communist Party. He is the president of his neighbourhood's Committee for the Defence of the Revolution, a 39-year-old island-wide organization often cited as playing a crucial role in perpetuating Mr. Castro's regime.

"The revolution has done a lot for the people of Cuba," says Mr. Martinez, who claims the block-by-block organization serves the purpose of helping needy neighbours, not monitoring people's attitudes and turning in dissenters, as it's known for. "Fidel has accomplished a lot, in spite of the blockade."

The U.S. embargo, frequently cited by Mr. Castro and his cohorts as the chief reason for Cuba's woes, began in 1962 after tensions crested in U.S.-Cuban relations. Mr. Castro believed his large northern neighbour planned to subvert the revolution. And, in fact, it tried.

The United States, the second country after Venezuela to recognize the revolutionary regime, quickly lost faith in Mr. Castro after his rebels executed about 200 Batista officials within three weeks (British historian Sir Hugh Thomas estimates Mr. Castro's government executed 5,000 people by 1970), expropriated almost all U.S. and foreign-owned property, and began shutting down critical media and silencing other critics.

Four decades later, the now 72-year-old Cuban leader has survived multiple invasions including the botched U.S.-planned 1961 Bay of Pigs assault, countless assassination attempts that included CIA-engineered exploding cigars, and the isolation and enmity of eight U.S. presidents.

Today, Mr. Castro is credited by loyalists like Mr. Martinez with significantly improving the island's healthcare and education systems. The defiant ruler himself often boasts of his regime's success in dramatically lowering the island's infant mortality rate to 7.2 per 1,000 births, boosting life expectancy to 75.3 years and increasing the number of doctors to one per 160 people.

Mr. Castro also touts such education advances as the island's nearly 96-per- cent literacy rate, the highest in Latin America, one teacher for every 13.7 students and one of the highest enrollment rates in the hemisphere -- 96 per cent of all students go through to the Grade 6.

But because of the government's lack of accountability, critics question the reliability of Mr. Castro's numbers. Doubts have long been raised about the quality of doctors' training and the value of an education heavily influenced by party doctrine.

"There's really no way to prove what the government publishes, and statistics are definitely distorted in a favourable way," said Diosmel Rodriguez Vega, a former government statistician forced last year into exile in Miami. "There is pressure to make the revolution appear to be succeeding."

There is also the "Animal Farm" effect, or the tendency for the Communist Party to rewrite history, when convenient, in a way similar to the pigs in George Orwell's classic allegory. Most recently, for example, the party announced that the revolution was never anti-religious, despite years of exiling priests, persecuting worshipers and banning believers from its ranks.

Another example is the long-reviled tourism industry. When Mr. Castro came to power, he denounced tourism as a symbol of Batista-era decadence and for spawning rampant prostitution. Today, however, Cuba welcomes more than twice as many tourists as it did before Mr. Castro -- with about 1.2 million visitors pumping in $1.5 billion in 1997 -- and the resurgence of prostitution has helped make the communist island popular for "sex tourism."

Other such examples abound. But the most glaring one is the widespread use of U.S. dollars, formerly the symbol of all evil in Communist Cuba. Once a crime that brought time in jail, now Cubans can barely survive without using dollars. The average monthly salary of 207 pesos -- $9.85 -- doesn't buy much in Cuba, where everything from soap to toilet paper is hard to get unless bought in stores that only accept dollars.

"It's so pathetic really after 40 years that Cuba has become what it has become," says Ninoska Perez, of the powerful anti-Castro Cuban American National Foundation in Miami. "It's really like Animal Farm with all the contradictions. Cubans can build hotels but they can't stay in them. Children after seven years can't get fresh milk, but tourists can have it whenever they want. Is that the paradise Castro had in mind?"

Beneath the awnings of the Maximo Gomez Domino Club off Calle Ocho (Eighth Street) in Miami's Little Havana, clumps of counterrevolutionaries -- aging men who have schemed much of their lives to end Mr. Castro's rule and still dream of returning to their tropical homeland -- slap scuffed dominoes on stone tables and mutter in Spanish.

Norberto Pino, a 70-year-old retired factory worker who fled Cuba in 1962, like the many exiles who come here to play dominoes or cards, once was a fervent supporter of the revolution. He even named his son Fidel and daughter Victoria Libertad, who was born the same day Mr. Batista escaped and the revolution triumphed. But like Mr. Gonzalez, his enthusiasm soon soured.

Now he passes his days pining for his country and playing hands of gin rummy. Behind him is a painted mural of presidents and prime ministers from the Americas. Leaders from Chile to Canada are depicted in colourful hues. But one country's head of state is missing: Cuba's Castro.

"I have four brothers and cousins who still live on the island, and they have nothing," Mr. Pino says. "It's (Castro's) fault. And my daughter and son have to live with the mark of the revolution every day. It's a shame what has happened."

Course of the revolution:

- Jan. 1, 1959: Dictator Fulgencio Batista flees and Fidel Castro's rebels take power.

- May 17, 1959: A land reform law leads to friction with United States.

- February 1960: Soviet Foreign Minister Anastas Mikoyan visits Cuba and signs sugar and oil deals. They were the first of many pacts during next 30 years.

- June 1960: Cuba nationalizes US-owned oil refineries after they refuse to process Soviet oil. Nearly all other US businesses are expropriated by October.

- July 6, 1960: President Eisenhower slashes US import quota for Cuban sugar.

- October 1960: Washington bans exports to Cuba, other than food and medicine.

- Jan. 3, 1961: The US Embassy in Havana closes.

- April 16, 1961: Castro declares Cuba a socialist state.

- April 17, 1961: Almost 1,300 Cuban exiles supported by the CIA invade at Bay of Pigs; the attack collapses two days later.

- Jan. 22, 1962: Cuba is suspended from the Organization of American States; Cuba responds with call for armed revolt across Latin America.

- Feb, 7, 1962: Washington bans all Cuban imports.

- March 19, 1962: Food rationing begins in Cuba.

- October 1962: President Kennedy blockades Cuba to force the removal of Soviet nuclear-armed missiles; Soviets agree within days and Kennedy agrees privately not to invade Cuba.

- March 1968: Castro's government takes over almost all private businesses other than small farms.

- July 1972: Cuba joins Comecon, Soviet-led economic bloc.

- November 1974: High-level US and Cuban officials open secret talks; the effort to improve ties fails.

- April 1980: A refugee crisis starts at the port of Mariel as Cuba says it will let anyone leave; about 125,000 flee by the end of September.

- December 1984: A US-Cuba immigration agreement is signed.

- December 1991: The collapse of the Soviet Union ends extensive aid to and trade with Cuba, whose economic output plunges 35 percent by 1994.

- Aug. 14, 1993: Cuba ends a ban on the use of dollars, encouraging Cubans to receive funds from abroad and from a growing tourism industry. Small-scale private businesses are legalized in September.

- October 1992: Congress tightens the US embargo of Cuba.

- August 1994: Castro declares he will not stop Cubans trying to leave; about 40,000 take to the sea heading for United States. An expanded US-Cuba migration agreement is signed in September.

- Oct. 1, 1994: Private farmers' markets are created to help solve food shortages.

- Feb. 24, 1996: Cubans shoot down planes operated by the dissident group Brothers to the Rescue.

- March 12, 1996: The US Helms-Burton Act imposes penalties on foreign companies using confiscated US property in Cuba.

- January 1998: Pope John Paul II visits Cuba.

which opened in April, is the first 18-hole golf course to be built in Cuba since the revolution triumphed in 1959. At least six more golf courses are being planned throughout the island, Garcia said.

which opened in April, is the first 18-hole golf course to be built in Cuba since the revolution triumphed in 1959. At least six more golf courses are being planned throughout the island, Garcia said.